|

|

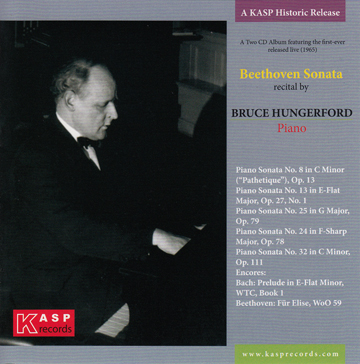

KASP 57741 — Live Beethoven Sonata Recital with Encores by Bach and Beethoven $ 16 plus shipping (CD) Click here to BUY from the KASP website In a 1969 High Fidelity article, comparing several ongoing complete Piano Sonata cycles being readied for the upcoming Beethoven Bi-Centennial, the noted critic, Harris Goldsmith, wrote "Vanguard's entry features Bruce Hungerford, a relative dark-horse competitor who, on the basis of his so-far released recordings, may well end up with top honors." Although he was not unknown before the early and mid 1970's, that was the time when the reputation of the Australian-born Hungerford (1922-1977), a student of Ignaz Friedman, Ernest Hutcheson and Carl Friedberg, soared rapidly among music and record lovers. His participation in the 1970 Hunter College (New York) benefit for the International Piano Library (now the International Piano Archives at Maryland, or IPAM) is still recalled by some. He played only a group of Schubert Ländler on a program filled with brilliant works, performed by pianists such as Earl Wild, Jorge Bolet, Raymond Lewenthal, Alicia DeLarrocha and Guiomar Novaes. But the depth, soulfulness, and beauty of his performance made those "simple" pieces among the highlights of the concert. Bruce Hungerford played all-Beethoven recitals at New York's Town Hall in 1970, and at Alice Tully Hall in 1974. (Pianist Alfred Brendel was spotted in the audience at the latter.) Also, during that period, he joined the faculties of Mannes College of Music and the New York State University at Purchase. His Vanguard records were played regularly on the radio, and anyone in New York who listened to classical music knew his name. Then, in the early hours of January 26th, 1977 he died, together with three family members, in an auto accident caused by a drunk driver in a larger vehicle who came across the road, hitting them head-on. Gradually, as happens with time, especially in the case of one who was slow to receive the recognition he deserved, the memory of this artist faded. The cornerstone on which his recorded legacy lies is the Vanguard series of his incomplete Beethoven cycle (22 of the 32 sonatas) plus one disc each of music by Schubert, Chopin and Brahms, and a wonderful IPAM recording of live Schubert performances. Other material, which one hopes will eventually be released, includes his recording of the complete piano works of Richard Wagner (previously released on LP's), earlier private recordings which include the music of Bach, and his recordings of lessons with his teacher, Carl Friedberg, who knew Brahms and Clara Schumann. Although, in his mature years, he was acknowledged for his mastery of the music of all the composers mentioned above, the one with whom his name was most often associated is Beethoven. And his work as a Beethoven pianist was compared to that of the greatest Beethoven interpreters. This recording is the first release of a live, Bruce Hungerford all-Beethoven piano recital. It was recorded in 1965 at the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth (a hugely elaborate rococo auditorium, predating Richard Wagner's arrival in Bayreuth by more than a century). This former student remembers Bruce Hungerford saying that he studied a work seven times before performing it. This probably explains why the sonata cycle was still incomplete at the time of his death, at least eight years after he started recording it. One regrets never hearing the sonatas he didn't get to, especially as he had never performed the whole cycle. The greatest loss, perhaps, is that he didn't live to perform or record the mighty Hammerklavier. But clearly, he was working on it at the end, as the score was found on the music rack of his piano when his studio was opened after the accident. It would not be an exaggeration to describe his Beethoven playing as combining the intensity and technical brilliance of Rudolph Serkin with the warmth, beauty of tone and profundity of Artur Schnabel. Fast movements were usually played quite fast and slow movements were slow, though never static, and demonstrated a rare depth of feeling, and expression. The spirituality of his playing was often mentioned. Some moments even seem magical. One thinks of the way he ends the first movement of the G Major Sonata, Op. 79, tossing it up in the air where it evaporates, or his playing of the surprise ending of the last movement, where he graciously and politely sets it down. Or of the "arrival in heaven" in the last movement of Op. 111, just before the great (triple) trills. The audience reaction at the end of Op. 111 is exactly what one would wish for from an appreciative audience. After an achingly long wait, he plays the unbelievably soft and perfectly focused final chord. It's about 10 long seconds after he finishes playing before anyone wants to break the spell he has set by clapping. Then, after almost a minute of spirited applause, all hell breaks loose, probably as he returns to the stage for another bow, and the audience gives a full-throttled response. Although he usually played Bach's Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring, in the arrangement of his friend and mentor, Dame Myra Hess, after Op. 111, on this occasion his first encore is the E-Flat Minor Prelude from the First Book of the Well-Tempered Clavier. Slow, deeply thoughtful, and with some of those amazing harmonic twists with which Bach sometimes startles, it continues the mood of reverence. Finally, he sends his audience home with a performance of Beethoven's often hackneyed Für Elise, played with a simplicity, dignity and elegance that reminds you what a beautiful work this is. —Donald Isler Pianist Antonio Iturrioz said of this recital: I could write an essay of the experience I received listening to this great Beethoven interpreter! ... It has been so many years since I have heard such profound and mysterious Beethoven. And at the same time very direct and simple ... I said to myself, this is one of the very few real Beethoven messengers ... He had such a beautiful sound combined with his unbelievable depth of expression. One of the truly great Beethoven players of all time!

MusicWeb International wrote: Listening to the 1965 all-Beethoven recital confirms for me, without any reservations, Hungerford's reputation as a great Beethoven player — one in a long list that includes, amongst others, Schnabel, Nat and Kempff. The venue for the concert is the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth, Germany, the date 29 July. The pianist kicks off with the Pathétique Sonata and, despite its familiarity, the performance never sounds jaded. The opening Grave is dark and dramatic, and leads into to an Allegro of energy and gusto. I am particularly taken with the precision and clarity of the mordents in the second subject. The Adagio is ethereal and the Rondo high-spirited. I am pleased that he opted for Op. 27 No. 1 rather than the Moonlight. There is a strong sense of fantasy throughout. The slow movement has an ardent sincerity, and in the brisk finale he truly achieves the tingle factor. Two short sonatas, No. 25 followed by 24, precede the Op. 111. The former is invested with generous helpings of wit and good humour. It is a treat to hear these two live, as they are rarely programmed. ClassicsToday.com wrote of this album: Between 1965 and his death in a 1977 car accident Bruce Hungerford recorded 22 out of the 32 Beethoven piano sonatas for Vanguard that count among the most stylish and intelligent interpretations one can find. The main program of this previously unpublished July 29, 1965 recital from the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth replicates repertoire that Hungerford eventually would record in the studio, yet the presence of an audience arguably elicits added breadth and spontaneity. For example, the F-sharp major sonata finale's rapid major and minor key alternations are timed to more humorous effect, the “Pathétique” sonata outer movements reveal a larger number of bass lines brought to the fore, and the Op. 27 No. 1's Allegro molto vivace loosens up with a giddy, Schnabel-like abandon that Hungerford slightly tempered in the studio. If Op. 79's Presto alla tedesca is a shade stiff and square, the Vivace's playful simplicity and suppleness again evokes Schnabel's still-unrivaled paradigm. If Schnabel enveloped Op. 111's first-movement Allegro con brio in a headlong, sweeping haze, Hungerford projects comparable energy while clearly untangling the gnarly counterpoint. The pianist's Arioso distinguishes itself with a muted, spaciously sculpted theme, unified tempo relationships from one variation to the next, precise yet never rigid articulation, and long chains of trills that are so beautiful that you don't want them to end! For encores, Hungerford plays a slow, grim, and rivetingly rhythmic Prelude in E-flat minor from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier Book I, followed by a simple, direct, and understated Beethoven Für Elise. The only drawback to this recital concerns the dry, overmodulated sonics, which suggest that someone had turned the tape recorder input levels up excessively high, or placed the microphones too close to the piano, while the audience applause seems to come from another venue. After Hungerford finished Op. 111, the audience waited 10 seconds before applauding for about two minutes. I can understand the documentary purpose of preserving such an audience response, but I suspect most listeners will bypass it and go directly to the encores, as I did. Ultimately this release will appeal more to specialists with a strong interest in Hungerford than general audiences, but anyone who cares about the Beethoven sonatas will gain insights from this pianist's artistry. Producer Donald Isler, a Hungerford pupil and an excellent pianist in his own right, contributes informative and affectionate booklet notes. —Jed Distler And the Audiophile Audition said: A first release of a Bruce Hungerford all-Beethoven recital from 1965 reminds us what fate (his untimely death in a car collision) stole away cruelly in terms of a first-class musical practitioner. KASP records resurrects a Beethoven program Hungerford gave 29 July 1965 at the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth, Germany. Despite sonic limitations, the recital confirms Hungerford's repute as a seriously devout artist, committed to a repertory that extended well beyond Beethoven to embrace his much-revered Romantics. The Pathetique Sonata betrays surface hiss and pre-echo, but the solemnity and drive of the performance more than compensate for thin or shaky sound. A mixture of chromatic pain and diatonic will, the first movement — with repeat — achieves a driven momentum reminiscent of Rudolf Serkin but softened by the Carl Friedberg school of keyboard sonority. The Adagio cantabile proves particularly touching, songful, and intimately attuned to the symmetry of the phrasing. The "recovered context" of the Rondo: Allegro projects studied velocity and great delicacy of color nuance. The clean articulation in Hungerford's staccato attacks require careful listening. A blithe serenity of style secures this eminently graceful rendition that lacks nothing for passionate intelligence. Beethoven's 1801 E-flat Sonata Quasi Fantasia, overshadowed by its companion, the "Moonlight," offers Hungerford numerous opportunities to articulate a number of diverse style and keyboard effects. Hungerford can be quite explosive, as clearly evident in his punishing sforzati that intrude on what had been a ruminative opening movement. The improvisatory fleetness and occasional vehemence proceed into the brief Allegro molto vivace, a movement that pits harp effects against drums. A rollicking march ensues, finished off by a mighty trill. A thoughtful, lovely, even somberly ominous Adagio con espessione leads into an Allegro assai rife with contemplative cadenzas and learned counterpoint. Hungerford does not spare the velocity of this bravura movement, a tour de force for sheer sonic contrasts. The eminently, playfully compressed G Major Sonata, Op. 79 (1809) combines brevity and Homeric wit. The first movement, attacked vigorously by Hungerford, presents a Presto alla tedesca, an impish German country dance. Hungerford's blithe personality shines in this movement. He proceeds to the rocking Andante, a model for Mendelssohn gondolier songs, with its poignant melodic content. The last movement Vivace utilizes a progression that adumbrates the first movement of Op. 109. Hungerford alternately makes his keyboard sound like a music-box or a manic zither, a masterpiece of ingenious improvisation delivered by a master. The Sonata No. 24 in F-sharp Major (1809) has won diverse adherents, from Claudio Arrau to Egon Petri. Beethoven himself expressed a partiality for its lyric fragments and often stunning harmonic progressions. Hungerford plays the four-measure Adagio cantabile as an upbeat to the graceful Allegro that proceeds in sonata-form. Transparency of touch marks Hungerford's performance as the theme sojourns through various registers and dynamic shifts. The last movement, Allegro vivace, opens with trumpets and moves hectically through knotty scales and brilliant runs. A far cry from the Appassionata Sonata, this music still manages to alert our ears to a volatile personality behind the music. The culmination of Beethoven's two-movement sonata experiments lies in his Op. 111 C Minor Sonata (1822), which synthesizes a union of polar opposites. Hungerford opens (Maestoso) with pungent double-dotted chords that pave the way for the conflict that it will require the huge theme-and-variations movement to resolve. The passion of the ensuing Allegro's momentum becomes relentless, except for pregnant pauses and poco ritente that intrude on a voracious energy. Hungerford makes this movement remind us of the Fifth Symphony. That the hurtling masses of sound resolve into a pianissimo C Major proves just as miraculous as the frenetic counterpoints and pungent stretti that led us there. If titanic intricacy marks the first movement, C Major simplicity dominates the Arietta and its manifold permutations of evolution. If the Maestoso depicts an earth-bound agon, the expansive second movement details the various stages of spiritual transformation possible to an exalted soul. That the sublimity of the music may absorb wonderful wit occurs in Hungerford's potent realization of the third variation, with its presentiments of American boogie-woogie. Only variation five moves away to a foreign key, having followed an episode of trills, returning to the theme in its original form. The uncanny blend of movement and stasis Hungerford achieves with ever lighter applications of diminuendo contrasted against wonderfully flowing arpeggios. The final evolution moves towards the dominant G, surrounded by trills and occasional peals of some distant tone that would call to Schumann. Despite the occasional crescendos, we feel the material world divested of its content, and a true apotheosis of the spirit flows from Hungerford. After the last chord and a much-hovering awe, the unanimous applause erupts for a mighty interpretation of this seminal opus. The Bach Prelude in E-flat Minor proffers another exploration of profound simplicity of expression, and the ubiquitous Bagatelle in A minor "Für Elise" regains an original innocence. —Gary LemcoKASP 57741: KASP 57741 — Live Beethoven Sonata Recital with Encores by Bach and Beethoven $ 16 plus shipping (CD) |